If you're taking medication for high blood pressure, you might be surprised to learn that something as simple as black licorice candy could be working against your treatment. It's not just a myth or old wives' tale - there's solid medical evidence showing that licorice, especially the kind containing glycyrrhizin, can make your blood pressure meds less effective, raise your blood pressure, and even cause dangerous drops in potassium. This isn't about occasional snacking. It's about real, measurable risks that show up in labs, hospital rooms, and clinical guidelines.

How Licorice Actually Affects Your Blood Pressure

Licorice root contains a compound called glycyrrhizin, which your body breaks down into glycyrrhetic acid. This metabolite blocks an enzyme in your kidneys called 11β-HSD2. That enzyme normally protects your body from cortisol - a stress hormone - binding to mineralocorticoid receptors. When that enzyme is blocked, cortisol acts like aldosterone, a hormone that tells your kidneys to hold onto salt and water and flush out potassium.

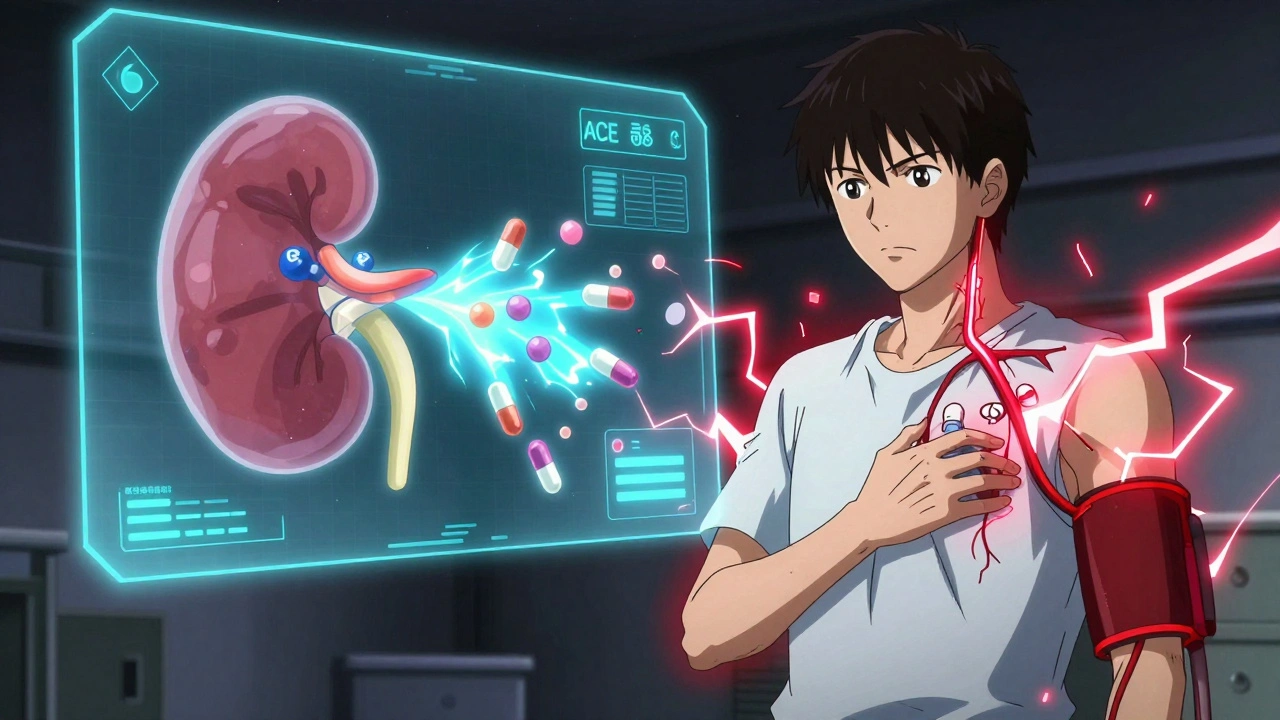

That’s bad news if you’re on blood pressure medication. Holding onto salt and water increases your blood volume. More volume means higher pressure in your arteries. Your meds - whether they’re ACE inhibitors, diuretics, or calcium channel blockers - are designed to lower that pressure. But if your body is holding onto extra fluid, those drugs can’t do their job properly.

Studies show that people who regularly consume high amounts of glycyrrhizin see their systolic blood pressure rise by an average of 5.45 mmHg. That might not sound like much, but in someone with already uncontrolled hypertension, that small spike can push them into dangerous territory. Add in the potassium loss - often 0.5 to 1.0 mmol/L lower than normal - and you’ve got a recipe for muscle weakness, irregular heartbeat, and even heart failure.

Which Blood Pressure Medications Are Most Affected?

It’s not just one type of medication. Licorice interferes with nearly all classes of antihypertensives, but the risks vary.

- Diuretics like hydrochlorothiazide or furosemide already make you lose potassium. Add licorice, and you’re doubling down on that effect. This combo can lead to severe hypokalemia - potassium levels below 3.0 mmol/L - which can trigger dangerous heart rhythms.

- ACE inhibitors like lisinopril or captopril help relax blood vessels and reduce fluid buildup. But licorice’s salt-retaining effect directly cancels out that benefit. Many patients see no improvement in blood pressure despite taking their meds - and the culprit turns out to be daily licorice tea or candy.

- Digoxin (Lanoxin) is especially risky. Low potassium makes your heart more sensitive to digoxin. Even normal doses can become toxic. There are documented cases of older adults developing heart failure after using herbal laxatives containing licorice while taking digoxin.

- Potassium-sparing diuretics like spironolactone or eplerenone are meant to keep potassium up. But licorice forces potassium out anyway, making these drugs less effective and increasing the risk of rebound hypertension.

The Merck Manual and MSD Manual both warn that patients with hypertension should avoid licorice entirely. That’s not a suggestion - it’s a clinical red flag.

How Much Licorice Is Too Much?

You don’t need to eat a whole bag to cause trouble. The widely accepted safety threshold is 100 mg of glycyrrhizin per day. That’s about 60 to 70 grams of traditional black licorice candy - roughly 2 to 2.5 ounces. But here’s the catch: not all licorice products are the same.

Many modern candies labeled as "licorice" actually use anise oil for flavor and contain zero glycyrrhizin. They’re safe. But if you’re eating:

- Traditional black licorice candy (especially imported or artisanal brands)

- Licorice root tea

- Herbal supplements labeled as "licorice root" or "Glycyrrhiza glabra"

- Some tobacco products or throat lozenges

...you could be getting a hidden dose of glycyrrhizin. And since the FDA doesn’t require manufacturers to list glycyrrhizin content on labels, you’re often flying blind.

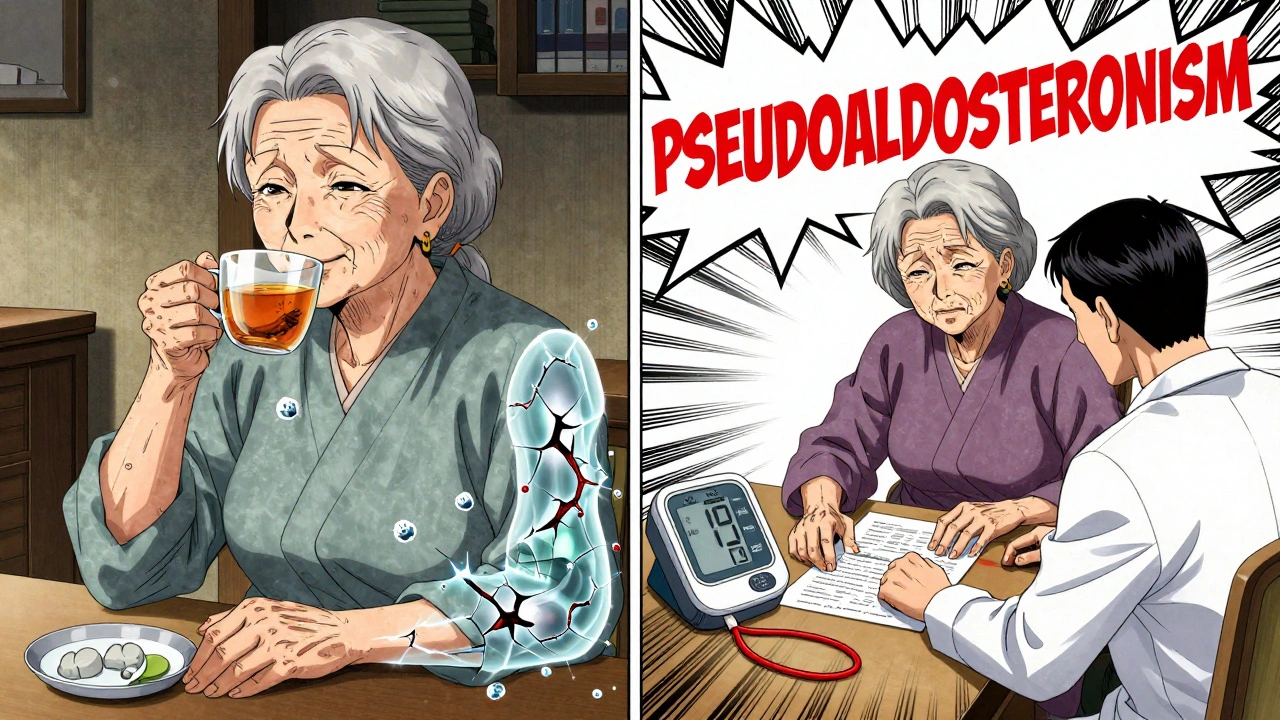

Also, sensitivity varies. Women, older adults, and people with existing high blood pressure are more vulnerable. One person might eat a small piece of licorice daily and feel fine. Another - say, a 72-year-old woman on lisinopril - could develop muscle weakness and elevated blood pressure after just two weeks of similar consumption.

What Symptoms Should You Watch For?

If you’re on blood pressure medication and start noticing any of these, consider licorice as a possible cause:

- Unexplained rise in blood pressure, even while taking meds regularly

- Fatigue or muscle weakness - especially in legs or arms

- Palpitations or irregular heartbeat

- Swelling in ankles or feet (edema)

- Headaches or dizziness

- Extreme thirst or frequent urination

These aren’t vague symptoms. They’re classic signs of pseudoaldosteronism - the medical term for what licorice does to your body. Doctors test for it by checking your cortisol-to-cortisone ratio and measuring plasma renin and aldosterone levels. If those are off, and you’ve been eating licorice, the connection is almost always clear.

What Should You Do?

If you’re taking blood pressure medication:

- Stop eating black licorice candy unless you’re certain it’s glycyrrhizin-free. Look for labels that say "anise-flavored" or "no real licorice root."

- Avoid licorice root tea and herbal supplements. Even "natural" doesn’t mean safe when it comes to drug interactions.

- Talk to your doctor if you’ve been consuming licorice regularly. Ask for a basic blood panel - especially potassium and sodium levels.

- Read supplement labels carefully. Licorice root is often hidden in formulas for digestion, stress, or adrenal support. If you see "Glycyrrhiza glabra," skip it.

- Give it 2-4 weeks after stopping licorice to see if your blood pressure improves and potassium levels normalize. In many cases, the effects reverse once the compound is cleared from your system.

There’s no need to panic if you’ve had a piece of licorice once in a while. But if it’s become a daily habit - whether you think it’s "just a treat" or "a natural remedy" - you’re playing with fire.

Why This Interaction Is Often Overlooked

Doctors don’t always ask about herbal products or candy habits. Patients don’t always think of licorice as a "drug." But this interaction is well-documented, predictable, and preventable.

Healthcare systems in New Zealand and Australia have issued formal warnings based on Medsafe’s 2019 bulletin. The American Heart Association doesn’t have a standalone guideline, but it references the 100 mg/day limit in clinician training materials. The problem? Most people don’t know to look for it.

Unlike grapefruit, which has clear warnings on prescription bottles, licorice has no such labeling. You have to know to ask. And that’s why so many patients end up with uncontrolled hypertension - not because their meds aren’t working, but because something they ate every day was quietly sabotaging them.

What About Red Licorice or "Sugar-Free" Licorice?

Red licorice - the kind that’s often strawberry or cherry-flavored - typically contains no licorice root at all. It’s just artificial flavoring and coloring. Same goes for many "sugar-free" or "diet" versions. They’re generally safe.

But don’t assume. Always check the ingredient list. If you see "licorice extract," "glycyrrhizin," or "Glycyrrhiza glabra," avoid it. If it says "natural flavor" or "anise oil," you’re probably fine.

And remember: herbal teas marketed for "digestion" or "liver support" often contain licorice root. Just because it’s sold as a "herbal remedy" doesn’t mean it’s harmless - especially when you’re on prescription meds.

Bottom Line

Licorice isn’t just a candy. For people on blood pressure medication, it’s a hidden risk with real, documented consequences. The science is clear: glycyrrhizin raises blood pressure, lowers potassium, and undermines the effectiveness of common antihypertensive drugs. The threshold for harm is low - 100 mg per day - and the effects build up over time.

If you’re managing high blood pressure, skip the black licorice. Read labels. Ask your doctor. And don’t assume "natural" means safe. Your blood pressure depends on it.

I had no idea licorice could mess with my blood pressure meds. I eat that stuff like candy every week. Guess I'm switching to the red stuff now. 😅

This is a critical public health message that deserves far more visibility. Many patients are unaware of this interaction.

OMG I just read this and Ive been drinking licorice tea for my 'digestion' for 3 years?? I think my ankles are swallen bc of this?? 🤯

This is one of those things that sounds like a myth until it hits you in the face. I had a patient last month whose BP wouldn't budge-turns out he was eating licorice root gummies daily thinking they were 'natural support'. He was shocked when his potassium dropped to 2.8. We need more of these wake-up calls.

I work in pharmacy and I see this all the time. People think herbal = harmless. Nope. Licorice root is basically a sneaky mineralocorticoid. And no one reads labels. I had someone bring me a bottle of 'adrenal support' with Glycyrrhiza glabra listed as ingredient #1. I told them to toss it. They came back two weeks later saying their BP was normal again. Wild.

It's crazy how something so small can have such a big effect. I used to love black licorice as a kid. Now I just think of it as a quiet saboteur. Good reminder to be mindful of what we think of as 'just snacks'.

Thanks for sharing this. I'm going to check my supplements tonight. I had no idea.

I eat licorice every day 😎 I'm fine 🤷♂️

The 100 mg/day glycyrrhizin threshold is well-supported by clinical studies. The FDA's lack of labeling requirements is a regulatory gap. Patients should be proactive. Always check for Glycyrrhiza glabra on ingredient lists-especially in teas, supplements, and ethnic candies. This interaction is preventable, predictable, and often reversible.

So let me get this straight. The same root that's been used for 4000 years to 'balance humors' is now a villain because some guy in a lab said so? 🤨 Maybe we should stop trusting white coats and start trusting grandma's tea.

I'm a nurse practitioner and I screen all hypertensive patients for licorice use now. It's one of the most common hidden culprits in treatment-resistant hypertension. I've seen full BP normalization within three weeks of stopping it. Simple, effective, and overlooked. Always ask.

In India we use mulethi for cough and digestion. I never thought it could interfere with meds. This post made me stop my daily mulethi tea. My BP dropped 8 points in two weeks. Mind blown. Thanks for the heads up!

I used to think this was just a rumor until my mom ended up in the ER with a weird heart rhythm. Turned out she was drinking licorice root tea for 'stress relief' and was on lisinopril. We almost lost her. This isn't hype. It's survival.

I'm not falling for this medical fearmongering. If I want my licorice, I'll have it. My BP is fine. Stop trying to control what people eat.

You're all overreacting. It's candy. If you can't control your BP with meds, maybe you need better meds-not to give up your favorite snack.