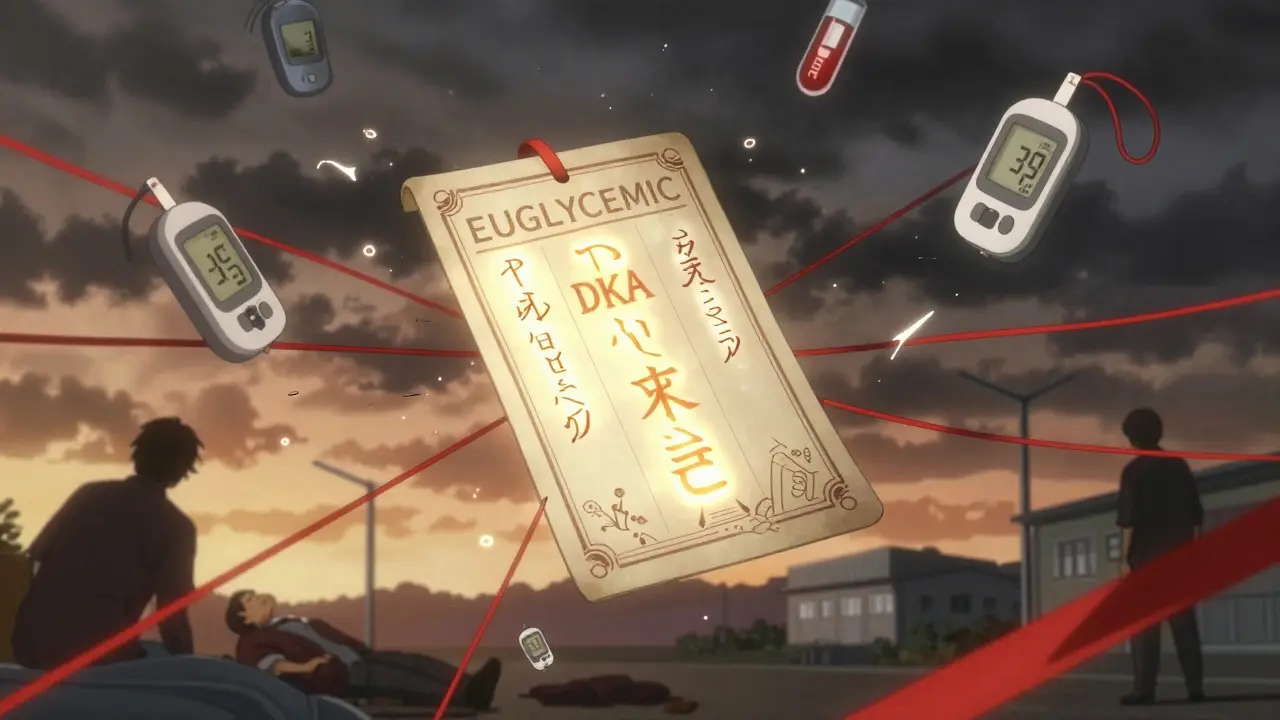

Euglycemic DKA Risk Assessment Tool

Assess Your Risk of Euglycemic DKA

This tool helps you evaluate if you might be experiencing euglycemic DKA (DKA with normal blood sugar). If you're on an SGLT2 inhibitor and have symptoms, seek medical attention immediately.

Risk Assessment Result

What to Do Next

Most people think diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) means high blood sugar. If your glucose is under 250 mg/dL, you’re probably safe-right? Wrong. In patients taking SGLT2 inhibitors like Farxiga, Jardiance, or Invokana, a dangerous form of DKA can happen even when blood sugar looks normal. This is called euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis, or EDKA. It’s not rare. It’s not theoretical. And if you miss it, it can kill.

What Is Euglycemic DKA?

Euglycemic DKA is diabetic ketoacidosis without the high blood sugar. You still get the same deadly mix: acidosis (blood pH below 7.3), low bicarbonate (under 18 mEq/L), and high ketones. But instead of glucose soaring past 300 or 400 mg/dL, it’s stuck between 100 and 250 mg/dL. That’s the trap. It looks like everything’s under control. But inside your body, your cells are starving for fuel. Your liver is pumping out ketones like a factory on overdrive. And you’re slipping into metabolic chaos-quietly.This isn’t new. The first major reports came in 2015, when doctors in the U.S. started seeing patients on SGLT2 inhibitors showing up in the ER with vomiting, fatigue, and deep breathing-but their glucose meters showed numbers that didn’t match the severity of their illness. The FDA quickly issued a warning. Since then, studies show EDKA makes up 2.6% to 3.2% of all DKA hospitalizations. Among SGLT2 users, the risk is 7 times higher than in non-users. And it’s not just people with type 1 diabetes. About 20% of cases happen in people with type 2 diabetes who’ve never had DKA before.

Why Do SGLT2 Inhibitors Cause This?

SGLT2 inhibitors work by making your kidneys flush out extra sugar. That sounds good-lower blood sugar, weight loss, better heart health. But here’s the hidden cost: when glucose leaves your body through urine, your body thinks it’s running low on fuel. Your pancreas responds by releasing more glucagon, a hormone that tells your liver to break down fat for energy. That’s fine… until it goes too far.At the same time, insulin levels drop just enough-not enough to stop fat breakdown, but enough to keep glucose from rising. The result? Ketones build up fast. Your body burns fat like crazy, but your blood sugar stays normal. It’s a perfect storm. And it’s made worse by things like skipping meals, getting sick, drinking alcohol, or having surgery. Even fasting for a colonoscopy can trigger it.

Studies using glucose clamping show that when you keep blood sugar stable during SGLT2 inhibitor use, glucagon doesn’t spike. That proves the link: it’s not the drug itself-it’s the low-carb state it creates. Your body doesn’t know the sugar is being flushed out. It just knows it’s running low.

How Do You Know You Have It?

The symptoms are the same as classic DKA: nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, deep rapid breathing (Kussmaul respirations), extreme fatigue, and confusion. You might smell acetone on your breath-but not always. Some patients don’t have the classic fruity odor because ketone levels are lower. That’s another reason people miss it.Here’s the kicker: patients often feel fine until they suddenly crash. One woman, 58, with type 2 diabetes, took Jardiance for two years. She had a cold, ate less, and skipped her morning coffee. Two days later, she collapsed at home. Her glucose was 180 mg/dL. She was in acidosis. Her ketones were 7.8 mmol/L. She needed ICU care. No one suspected DKA because her sugar wasn’t high.

Lab tests will show:

- Arterial pH under 7.3

- Bicarbonate under 18 mEq/L

- Anion gap over 12

- Beta-hydroxybutyrate above 3 mmol/L

- Normal or mildly elevated glucose (100-250 mg/dL)

Leukocytosis (high white blood cell count) is common-but that’s often from dehydration, not infection. Don’t mistake it for sepsis. And don’t wait for glucose to rise. If you’re on an SGLT2 inhibitor and you feel off, test your ketones.

Emergency Treatment: What to Do

Time is critical. EDKA kills faster than you think. The first step? Don’t assume it’s not DKA just because glucose is normal.Here’s what works:

- Stop the SGLT2 inhibitor immediately. No exceptions. Even if you feel better, keep it off until you’re fully recovered.

- Start IV fluids. Use 0.9% saline at 15-20 mL/kg in the first hour, then 250-500 mL/hour. Dehydration is severe. Your kidneys are flushed, your blood volume is low.

- Give insulin. Start at 0.1 units/kg/hour. But here’s the twist: you can’t wait for glucose to hit 300 before adding sugar. Start dextrose-containing fluids (like D5W) when glucose drops below 200 mg/dL. Otherwise, you risk crashing into hypoglycemia.

- Replace potassium. Even if your blood potassium looks normal, your total body stores are empty. You’ll lose it fast once insulin starts. Give 20-40 mEq of potassium per liter of IV fluid.

- Monitor ketones. Use serum beta-hydroxybutyrate, not urine strips. Urine ketones lag and can be misleading. Serum levels above 3 mmol/L mean you’re in trouble.

Most patients improve within 24-48 hours. But the mistake? Waiting. Too many patients are sent home with a diagnosis of “gastroenteritis” because their glucose was 190. They come back in cardiac arrest.

Who’s at Risk?

You might think only type 1 diabetics are at risk. Not true. SGLT2 inhibitors are approved for type 2, but they’re used off-label in 8% of type 1 patients. In those patients, DKA rates jump to 5-12%. That’s not a fluke-it’s a pattern.High-risk situations include:

- Illness (infection, flu, COVID-19)

- Reduced food intake (fasting, dieting, nausea)

- Surgery or major stress

- Pregnancy

- Alcohol use

- Insulin dose reduction (especially in type 1)

Even people with good HbA1c can get EDKA. One study found patients with HbA1c under 7% were just as likely to develop it as those with higher numbers. The drug doesn’t care how well you’ve controlled your diabetes. It only cares if you’re in a low-carb state.

Prevention: What Patients Need to Know

The best treatment is prevention. And it starts with education.Every patient on an SGLT2 inhibitor should be told:

- Stop taking the drug if you’re sick, fasting, or having surgery. Don’t wait. Don’t think it’s “just a cold.”

- Check ketones anytime you feel nauseous, tired, or have abdominal pain-even if your glucose is normal. Use a blood ketone meter. Urine strips aren’t reliable enough.

- Don’t skip meals. Keep eating carbs. Your body needs fuel.

- Know the warning signs. Nausea, vomiting, deep breathing, confusion-these aren’t just “flu.” They’re red flags.

- Carry a medical alert card. It should say: “On SGLT2 inhibitor. Risk of euglycemic DKA.”

The FDA now requires all SGLT2 packaging to include this exact instruction: “Stop taking this medication and seek immediate medical attention if you have symptoms of ketoacidosis, even if your blood sugar is normal.” That’s not a suggestion. That’s a lifesaving mandate.

The Bigger Picture

SGLT2 inhibitors are powerful drugs. They reduce heart failure, slow kidney disease, and help with weight. But they’re not risk-free. As of 2023, they make up 25% of all new diabetes prescriptions in the U.S. That’s millions of people. And while overall DKA rates have dropped 32% since 2015 due to better awareness, EDKA now makes up 41% of all SGLT2-related DKA cases. That means we’re getting better at spotting it-but it’s still happening.Research is moving fast. A 2023 study found that the ratio of acetoacetate to beta-hydroxybutyrate in the blood can predict EDKA 24 hours before symptoms appear. That could change how we monitor high-risk patients. Other studies are testing tools that combine HbA1c variability and C-peptide levels to identify who’s most vulnerable.

But right now, the answer is simple: if you’re on one of these drugs, and you feel wrong-test your ketones. Don’t wait. Don’t assume. Don’t let normal glucose fool you.

EDKA doesn’t announce itself with a blood sugar spike. It sneaks in. And if you’re not looking for it, you’ll miss it.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can you get euglycemic DKA without an SGLT2 inhibitor?

Yes, but it’s rare. Traditional DKA usually happens with high blood sugar. Euglycemic DKA is most commonly linked to SGLT2 inhibitors, but it can also occur in type 1 diabetes during insulin pump failure, prolonged fasting, or extreme alcohol use. Still, the majority of cases today are tied to these medications.

Should I stop taking my SGLT2 inhibitor if I’m sick?

Yes. If you have an infection, vomiting, diarrhea, or are fasting for a test or surgery, stop your SGLT2 inhibitor. Resume it only after you’re eating normally and feeling better. Never keep taking it when you’re not eating or are dehydrated.

Do I need to check ketones every day?

No. Only check ketones when you have symptoms like nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, unusual fatigue, or trouble breathing-even if your blood sugar is normal. If you’re on an SGLT2 inhibitor, keep a blood ketone meter at home. It’s not expensive, and it could save your life.

Is euglycemic DKA more dangerous than regular DKA?

It’s not necessarily more dangerous, but it’s more likely to be missed. That’s what makes it deadlier. Patients are often sent home with the wrong diagnosis. Emergency teams may not test for ketones because glucose is normal. Delayed treatment increases the risk of coma or death.

Can type 2 diabetics get euglycemic DKA?

Absolutely. In fact, about half of all EDKA cases happen in people with type 2 diabetes. Many had never had DKA before. This is why doctors now test for ketones in all diabetic patients on SGLT2 inhibitors who present with nausea or vomiting-regardless of their diagnosis.

What should I do if I suspect EDKA?

Stop your SGLT2 inhibitor immediately. Drink water. Test your blood ketones. If your ketone level is above 3 mmol/L or you feel worse, go to the ER. Tell them you’re on an SGLT2 inhibitor and you suspect euglycemic DKA. Don’t wait. Don’t wait for your sugar to spike. This is an emergency.

Wow, I had no idea this was even a thing. My uncle’s on Jardiance and just had a scary episode last month-thought it was food poisoning. Turns out his ketones were through the roof. This post saved his life. Thanks for laying it out so clearly.

Of course the pharmaceutical companies love this. Sugar gets flushed out, patients feel 'better,' and nobody checks ketones because the glucose looks fine. It’s a perfect profit loop. They don’t want you to know the truth: this drug is just a chemical distraction from real metabolic health.

Just a heads-up for anyone on SGLT2s: I’m an RN and I always tell my patients to keep a ketone meter in their medicine cabinet. It’s like a smoke detector for your metabolism. Cheap, easy, saves lives. I’ve seen too many people get sent home with 'gastro' and come back in DKA. Don’t wait for the sugar to spike.

It is a well-documented fact that the FDA’s warning is insufficient. Regulatory bodies are inherently compromised by industry influence. The true danger lies in systemic negligence, not individual error. Patients must be vigilant. This is not medicine-it is pharmacological roulette.

ME: *sips coffee, takes Farxiga*

MY BODY: *starts making ketones like a startup on a funding spree*

GLUCOMETER: 'All good bro 😎'

ME: 'I feel weird though...'

EMERGENCY ROOM: 'You were 3 hours from a coma.'

Yeah. I’m keeping a ketone meter now. 🚨💀

Man, I’ve been on Invokana for 3 years and never knew this was lurking. I thought ketoacidosis was only for Type 1s. But after reading this, I checked my ketones last week when I had a cold-was at 2.1 mmol/L. Scared the hell outta me. Now I’m on a strict 'no fasting, no skipping meals' rule. Also, got me a cheap ketone strip tester off Amazon. Best $25 I ever spent.

Shoutout to the doc who wrote this-this ain’t just info, it’s a lifeline. My cousin’s a doc in Mumbai and she’s already sharing this with her patients. We need more posts like this, not less.

And yeah, even if you're 'well-controlled,' don’t get cocky. Your HbA1c doesn’t know you skipped dinner. Your liver does.

My sister was misdiagnosed twice. She almost died. Now I carry her ketone strips in my purse.

One must question the clinical utility of SGLT2 inhibitors given the non-trivial risk profile. The data is clear: while cardiovascular benefits exist, they are marginal in low-risk populations. The cost-benefit analysis is skewed by marketing, not evidence. This is not innovation-it is iatrogenic risk repackaged as progress.

OMG I just realized I told my mom to keep taking her Jardiance when she had the flu last month 😭 I’m calling her right now to tell her to stop it and get a ketone meter. Thank you for writing this-I’m sharing it with my whole family. You’re a lifesaver 🤍