When there isn’t enough medicine to go around

Imagine you’re an oncologist. Two patients need carboplatin - the same stage of cancer, similar age, same prognosis. But there’s only one dose left. Who gets it? This isn’t science fiction. It’s happening right now in hospitals across the U.S. As drug shortages grow more frequent and severe, doctors, pharmacists, and nurses are being forced to make choices no one should have to make. And without clear rules, those choices become arbitrary, unfair, and deeply traumatic.

Why are drug shortages getting worse?

It’s not just bad luck. The problem has been building for years. In 2005, there were 61 drug shortages reported in the U.S. By 2023, that number had jumped to 319, according to the FDA. Most of these are critical injectable drugs - cancer treatments, antibiotics, anesthetics - things you can’t replace easily. A single manufacturer often controls 80% of the supply for a generic drug. If one factory has a quality issue, or a raw material shipment gets delayed, the whole country feels it.

Manufacturers aren’t always required to warn hospitals in advance. Even though the 2012 FDA Safety and Innovation Act asked them to notify regulators six months before a shortage, only 68% follow through. Meanwhile, hospitals are spending an average of $218,000 a year just managing these disruptions - buying expensive alternatives, rerouting supply chains, and dealing with the chaos.

What does ethical rationing actually look like?

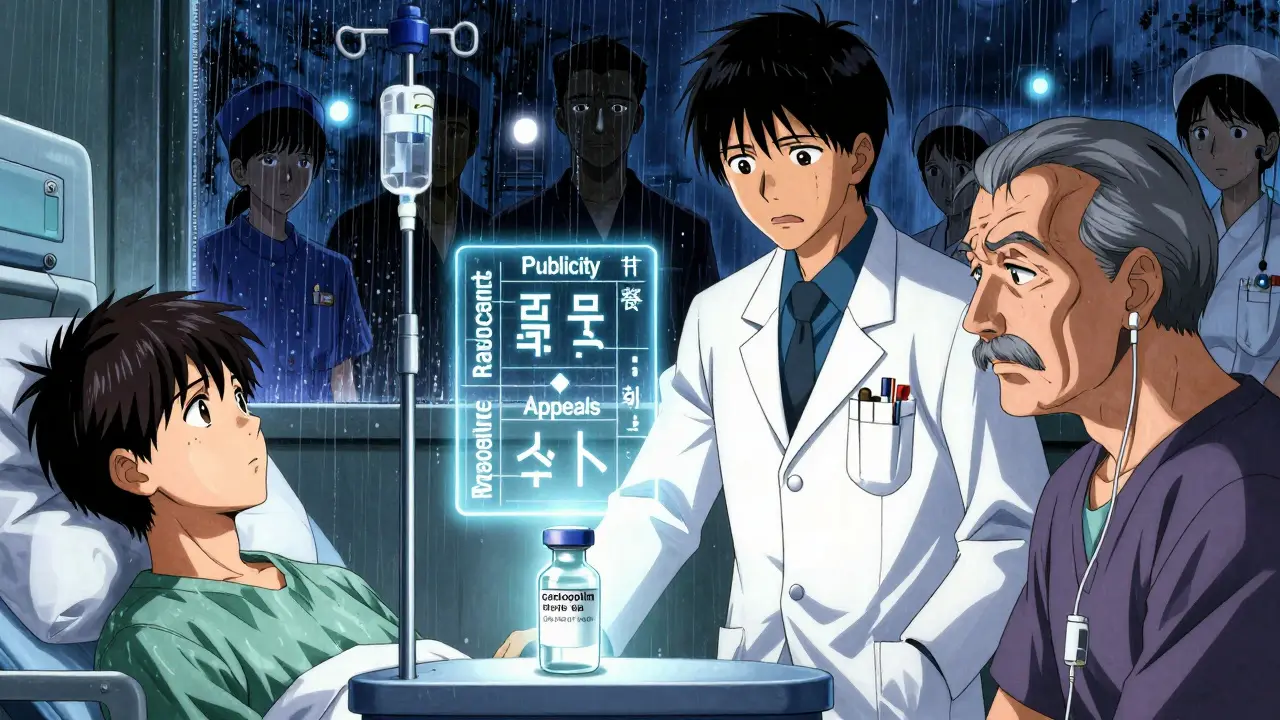

Ethical rationing isn’t about picking who lives or dies. It’s about making sure that when you can’t give everyone what they need, you do it fairly. The most respected framework comes from bioethicists Daniel and Sabin, called “Accountability for Reasonableness.” It has four rules:

- Publicity: Everyone must know how decisions are made.

- Relevance: Decisions must be based on medical evidence, not personal bias.

- Appeals: Patients or families can challenge a decision.

- Enforcement: There must be someone watching to make sure the rules are followed.

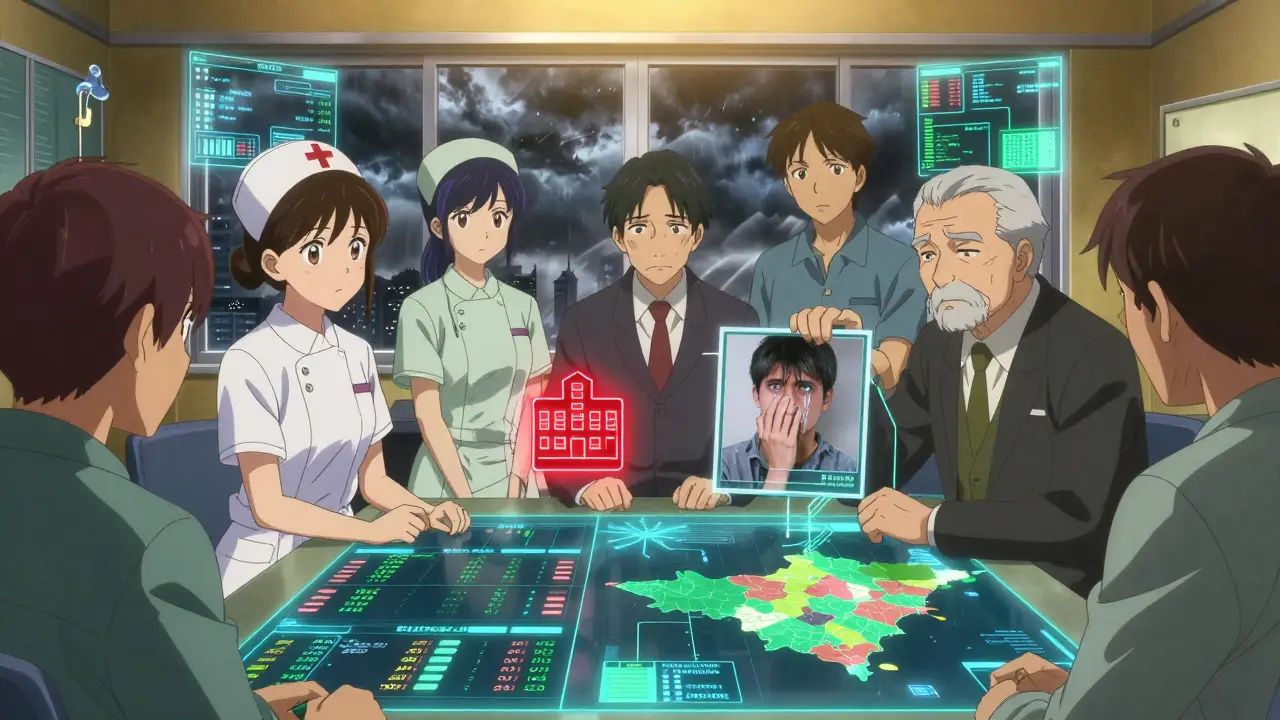

These aren’t just ideas. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) used them to create real guidelines for oncology drug shortages. Their 2023 guidance says allocation decisions should happen at the committee level - not at the bedside. A team of pharmacists, nurses, doctors, social workers, ethicists, and even patient advocates should meet to decide who gets what, based on clear criteria like:

- Urgency of need

- Chance of survival

- How many years of life the treatment might add

- Whether there’s a safe alternative

For example, Minnesota’s 2023 protocol for carboplatin and cisplatin says priority goes to patients getting treatment with curative intent - not just symptom relief - and only if no other drug works as well.

Why do most hospitals still get it wrong?

Despite the clear guidelines, most hospitals aren’t following them. A 2018 survey of 719 hospital pharmacists found only 36% had a standing committee to handle shortages. Of those, just 13% included doctors, and only 2.8% had an ethicist on the team. That means most decisions are still made by one doctor, in the middle of a crisis, with no backup.

This is called bedside rationing. And it’s dangerous. A 2022 JAMA Internal Medicine study showed that when decisions are made at the bedside, allocation disparities - meaning some groups get treated more than others - go up by 32%. It also leads to more burnout. Nurses and doctors who make these calls alone report 27% higher burnout rates. One oncologist told the ASCO forum: “I’ve had to choose between two stage IV ovarian cancer patients for limited carboplatin doses three times this month with no institutional guidance.”

Who gets left out?

Even when committees exist, they often ignore the people who need help the most. A 2021 Hastings Center Report found that 78% of rationing protocols don’t include any specific measures to protect marginalized communities - people of color, low-income patients, rural residents, or those without strong advocates. In rural hospitals, 68% have no formal rationing plan at all. Meanwhile, academic medical centers are better equipped, meaning the same drug might be available in Chicago but not in rural Kansas.

And patients? Only 36% are told they’re being rationed. That’s not just unethical - it’s a breach of trust. People have the right to know why they’re not getting a treatment. A 2021 Patient Advocate Foundation study recorded 127 formal complaints about undisclosed rationing. That’s not just a policy failure. It’s a moral failure.

What’s being done to fix it?

Change is slow, but it’s happening. In January 2024, pilot programs launched in 15 states to certify hospital rationing committees. These programs train teams on the Daniels and Sabin framework, require regular ethics training, and mandate patient communication protocols. The American Society of Bioethics and Humanities is leading this effort, aiming for national standards by 2026.

The FDA is also stepping in. Their October 2023 Drug Shortage Task Force announced plans for an AI-powered early warning system that could predict shortages before they happen - targeting a 30% reduction in duration by 2025. Meanwhile, ASCO launched a free online decision tool in May 2023 to help oncologists apply their ethical guidelines in real time.

And hospitals that do it right see real results. A 2022 Mayo Clinic study found that institutions with ethics-involved committees had 41% lower clinician distress scores. Patients reported feeling more respected. And disparities in care dropped significantly.

What can hospitals do today?

You don’t need to wait for national standards to start doing better. Here’s what works:

- Build a committee - even if it’s small. Include pharmacy, nursing, medicine, social work, and at least one ethicist.

- Adopt a clear framework - use ASCO or Daniels and Sabin. Don’t invent your own.

- Train your staff - 8 hours of ethics training and 4 hours of crisis communication can make all the difference.

- Track everything - document every rationing decision in the electronic health record. Include why it was made and whether the patient was informed.

- Communicate with patients - explain the shortage. Explain the criteria. Let them ask questions. Silence breeds fear.

What’s next?

The National Academy of Medicine is working on standardized ethical allocation metrics, with draft criteria expected in mid-2024. That could finally create a national baseline. But until then, hospitals have a choice: keep making decisions in the dark, or build systems that are fair, transparent, and humane.

The problem won’t go away. Drug shortages are projected to keep rising through 2027. The question isn’t whether we’ll ration - it’s whether we’ll ration with dignity.

Is it legal to ration medications?

Yes, rationing is legal when done through transparent, evidence-based protocols. The U.S. has no federal law banning it - but it does require that decisions avoid discrimination and follow ethical standards. Hospitals that ration without clear guidelines risk lawsuits and loss of public trust.

Can patients appeal a rationing decision?

They should be able to. Ethical frameworks like Daniels and Sabin require an appeals process. But in practice, only a small number of hospitals have formal procedures. Patients and families should ask for a written explanation and request a review by the hospital’s ethics committee.

Why don’t hospitals just buy more drugs?

Many drugs, especially generics, are made by just one or two manufacturers. If the factory shuts down, there’s no backup. Plus, hospitals buy in bulk through group purchasing organizations that prioritize low cost over supply security. Buying extra stock is expensive and risky - drugs expire, and storage requirements are strict.

Are there alternatives to rationed drugs?

Sometimes. For example, if cisplatin is unavailable, some oncologists use carboplatin instead - but it’s not always as effective. Other times, there’s no substitute. Rationing isn’t about finding alternatives - it’s about deciding who gets the limited supply that does exist.

How can I know if my hospital has a rationing plan?

Ask. Request a copy of the hospital’s drug shortage policy. If they don’t have one, or if they say decisions are made "case by case," that’s a red flag. Push for a formal ethics committee and transparent communication. Your voice matters.

I just read this and felt like someone punched me in the chest. I had a cousin go through chemo during a shortage and they gave her a less effective drug without telling her why. No one apologized. No one explained. Just silence. It breaks my heart that this is normal now.

But hey, at least we're talking about it. That's something.

This is so important! In India we face this too but with antibiotics and insulin. No one talks about it. Hospitals just say 'out of stock' and move on. We need global standards. We need transparency. We need to stop treating human lives like inventory.

Let’s make this a movement, not just a blog post.

The data presented here is statistically significant but methodologically flawed. The 319 shortage figure from the FDA includes minor formulations and compounded agents that are not clinically equivalent to the original product. Furthermore, the 2022 Mayo Clinic study has a small sample size and lacks multivariate control for hospital funding levels. The conclusion that ethics committees reduce distress by 41% is not causally established.

So let me get this straight. We’ve got a system where doctors are forced to play god because corporations won’t invest in redundant supply chains, and the solution is... more committees?

Wow. Just wow. At least the ethicists get paid overtime. Meanwhile, the nurse who has to tell a mom her kid won’t get the antibiotic because the factory in China had a power outage? She’s still getting $28 an hour and a pat on the back for being 'resilient'.

AMERICA IS WEAK. WE LET FOREIGN FACTORIES CONTROL OUR MEDS. WE NEED TO BRING BACK MANUFACTURING. MAKE DRUGS HERE. TAX THE OVERSEAS SUPPLIERS. BUILD MORE PLANTS. STOP BEING SOFT. WE’RE A SUPERPOWER - WHY ARE WE BEING BLACKMAILED BY A FEW CHEMICAL COMPANIES?? 🇺🇸💥

The ontological burden of distributive justice in pharmaceutical allocation is not merely a logistical or procedural concern-it is a hermeneutic crisis of the medical gaze. When the physician becomes the arbiter of viability, the clinical encounter is transmuted into a biopolitical calculus, wherein the body is reduced to a vector of utility. The Daniels and Sabin framework, while commendable in its proceduralism, fails to interrogate the epistemic violence inherent in the very act of quantifying life expectancy as a metric for allocation.

One must ask: Who authorizes the metric? And upon what moral ground does the hospital’s ethics committee derive its authority to adjudicate between two dying bodies?

I work in a rural clinic and we don’t have an ethicist. We don’t even have a full-time pharmacist. But we do have hearts. We sit together. We talk. We write things down. We tell patients the truth-even when it’s hard. It’s not perfect. But it’s human. And that’s more than most places are doing.

Let’s stop waiting for national standards. Start where you are. Talk to your team. Do the hard thing. It matters.

My mom was on cisplatin last year. They told us it was delayed. Never said why. Never said someone else got it. I didn’t even know rationing was a thing until I read this. We’re all just supposed to trust the system. But trust doesn’t fill prescriptions.

Thanks for saying this out loud.

As someone who works in pharma logistics in India, I can confirm: the real problem is not just one factory. It's the whole chain. Raw materials from China, packaging from Vietnam, shipping delays from the Red Sea, then hospitals ordering last minute because they didn't budget right. We need better forecasting, not just committees. And we need to pay nurses and pharmacists more so they don't burn out trying to fix what the system broke.

Also-yes, patients should be told. Always. Silence is cruelty.