When you pick up a prescription, you might not realize that the price you pay-or what your insurer pays-isn’t just set by the drug company. It’s the result of a quiet, high-stakes battle between buyers and sellers, where generic drug competition is the most powerful tool buyers have to drive prices down. In the U.S., generic drugs make up 90% of all prescriptions but only 22% of total drug spending. That’s not luck. It’s strategy.

How Generic Drugs Force Prices Down

When a brand-name drug’s patent expires, other companies can make identical versions-generic drugs. At first, there might be just one or two competitors. But as more manufacturers enter the market, prices don’t just drop a little. They collapse. A 2019 study found that when six generic versions of a drug are available, the price falls by an average of 90.1%. With nine or more, it drops to 97.3%. That’s not a trend. It’s a rule.

This isn’t theoretical. Take the cholesterol drug simvastatin. After its patent expired, over 100 generic makers started producing it. Within five years, the price per pill fell from $2.50 to less than 10 cents. That’s a 96% drop. The same thing happened with metformin, lisinopril, and dozens of other common drugs. The more competitors, the harder it is for any one company to hold onto high prices.

Who’s Doing the Negotiating?

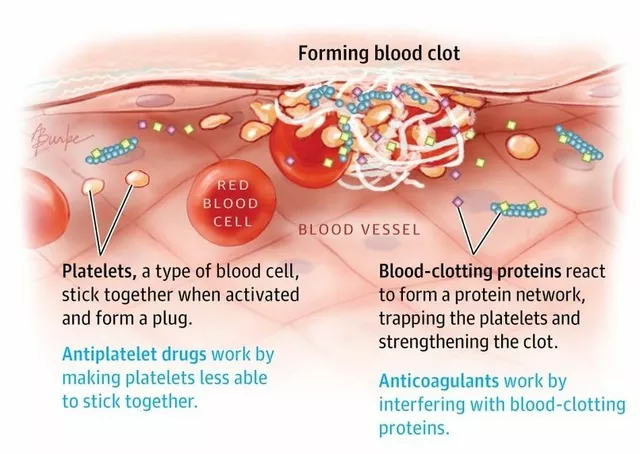

Buyers aren’t just individual patients. They’re big players: Medicare, Medicaid, private insurers, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), and even state governments. These organizations don’t just accept the sticker price. They use the threat-or reality-of generic competition to force lower prices.

For example, Medicare now has the legal power to directly negotiate prices for certain high-cost drugs under the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act. But here’s the twist: they can’t negotiate with drugs that already have generic versions on the market. Instead, they use those generics as benchmarks. If a brand-name drug costs $500 a month, but five generic alternatives sell for $15 each, Medicare starts its negotiation at around $15-$20. The brand company then has to justify why their drug is worth more. Often, they don’t.

Private insurers and PBMs do something similar, but behind closed doors. They use pricing data from the FDA’s Average Manufacturer Price (AMP) database and Medicare’s Prescription Drug Event (PDE) records to track how much generics are actually selling for. Then they tell brand manufacturers: “We’re going to pay what the generics charge, or we won’t cover your drug at all.”

How Other Countries Do It

The U.S. isn’t the only country using generic competition to control costs. Canada has had a tiered pricing system since 2014. If a drug has only one generic version, the government allows a higher price. But as more generics enter-say, five or more-the maximum allowed price drops sharply. It’s like a sliding scale based on competition.

Europe uses reference pricing. If a drug is sold in Germany, France, and the UK for $10, $12, and $8, respectively, regulators in another country might set the price at the lowest of those. This forces manufacturers to compete across borders. In the UK, a 2023 reform made this system even more dynamic, tying prices directly to what other European countries are paying.

These systems work because they don’t just rely on market forces-they actively shape them. They don’t wait for prices to fall. They make them fall faster.

What Happens When Competition Is Blocked?

But generic competition doesn’t always win. Sometimes, brand manufacturers use legal tricks to delay it.

One common tactic is “product hopping”-making a tiny change to a drug (like switching from a pill to a capsule) and pushing patients to the new version, which still has patent protection. Between 2015 and 2020, there were over 1,200 such maneuvers, according to the FTC. These changes don’t improve health outcomes. They just delay generics.

Another is “reverse payments.” A brand company pays a generic maker to stay out of the market. Between 2010 and 2020, the FTC found 106 cases where brand companies paid generics to delay entry. These deals cost U.S. consumers an estimated $3.5 billion a year in higher prices.

Even when generics do enter, some brand companies release their own “authorized generics”-versions made by the original company but sold under a different label. These undercut independent generics, keeping prices higher than they’d otherwise be.

The New Rules: Medicare’s Drug Negotiation Program

The Inflation Reduction Act changed the game in 2023. For the first time, Medicare can negotiate prices for 10 high-cost drugs starting in 2026. But the rules are strict: no negotiation if generics are already available. That’s intentional. The goal isn’t to replace competition-it’s to use it as a baseline.

CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services) doesn’t just look at one generic. They look at all therapeutic alternatives-drugs that treat the same condition, even if they’re not identical. They calculate the average 30-day cost of those alternatives and use that as the starting point. Then they adjust based on clinical data. If the brand drug offers no extra benefit, the price gets pushed down to match the generics.

According to CMS’s June 2023 guidance, they’re using real-world sales data from both AMP and PDE systems to make sure the generics they’re comparing against are actually being sold-not just approved. That’s key. A generic sitting on a shelf doesn’t help anyone. A generic in a patient’s hand does.

Why Generic Manufacturers Are Worried

It might sound like good news for patients. But for generic drugmakers, it’s complicated.

Some companies say that if Medicare sets a low price for a brand drug before generics even enter the market, it becomes impossible for them to compete. Why invest millions to develop a generic if the government has already capped the price below what you can profitably sell at? Avalere Health’s 2023 analysis found that this “chilling effect” could reduce generic entry by up to 40% in some cases.

Generic manufacturers also struggle with unpredictable pricing. In Europe, 78% of companies say they need stable, predictable pricing to justify investing in new production lines. But in the U.S., where prices can swing wildly after a new generic enters, many small manufacturers can’t afford to enter the market at all.

And then there’s the cost of making complex generics-like inhalers or injectables. These aren’t like simple pills. They require specialized equipment and testing. But current pricing models treat them the same as aspirin. That’s why some manufacturers say they’re being squeezed out before they even start.

What’s Working Right Now

Despite the challenges, the system works better than most people think. In 2023, the average price of a generic drug was $13.40 per 30-day supply. The average price for a brand-name drug? $245. That’s a 94% difference.

Patients who use generics save an average of $1,500 a year. For seniors on Medicare, that’s life-changing. The Association for Affordable Medicines estimates that generics saved U.S. patients $351 billion in 2023 alone.

And it’s not just about cost. It’s about access. When a drug gets generic, more people can afford it. More people get treated. More people stay healthy.

The Future: More Data, More Complexity

The next big shift is in how prices are set. Instead of just looking at what generics cost, buyers are starting to ask: “What’s the real value?”

Health technology assessment agencies are now planning to use real-world evidence-data from actual patient outcomes-to determine if a drug is worth its price. By 2025, 73% of these agencies say they’ll use this data in negotiations. That means a brand drug might be priced higher if it’s proven to reduce hospitalizations or improve quality of life. But if it’s just another version of the same thing? It won’t get a premium.

Meanwhile, biosimilars-generic versions of complex biologic drugs-are starting to enter the market. But they’re not catching on as fast. Only 45% of patients use them, compared to 90% for traditional generics. Why? Higher prices. Slower adoption. And less competition. That’s where the next big battle will be.

What This Means for You

If you’re a patient, ask your pharmacist: “Is there a generic?” If your insurer denies coverage for a brand drug, appeal. Use the existence of cheaper alternatives as your leverage.

If you’re a caregiver or advocate, push for transparency. Demand to know what prices insurers are paying. Support policies that speed up generic approval and block reverse payments.

If you’re a policymaker, remember: competition isn’t just a market force. It’s a public health tool. The more generics that enter, the more lives are saved-not just by lowering cost, but by making treatment accessible.

The system isn’t perfect. It’s still full of loopholes, delays, and corporate games. But the power of generic competition is real. And it’s working. Not because of goodwill. Because when there are ten companies selling the same pill, no one can charge what they want.

How do generic drugs lower prescription prices?

When multiple companies make the same drug after a patent expires, they compete on price. The more competitors, the lower the price. Studies show that with six generic versions, prices drop by about 90%. With nine or more, they fall to 97% below the brand-name price.

Can Medicare negotiate prices for drugs with generic versions?

No. Under the Inflation Reduction Act, Medicare cannot directly negotiate prices for drugs that already have generic versions on the market. But it can-and does-use the prices of those generics as a benchmark to set lower starting prices for brand-name drugs during negotiations.

Why do some generic drugs cost more than others?

Price differences come from manufacturing complexity, supply chain issues, and market competition. Simple pills like metformin cost pennies because hundreds of companies make them. Complex drugs like inhalers or injectables cost more because they’re harder to produce and fewer companies can make them.

What are reverse payments, and why do they matter?

Reverse payments happen when a brand-name drug company pays a generic manufacturer to delay entering the market. This keeps prices high. Between 2010 and 2020, the FTC found 106 such deals, costing consumers an estimated $3.5 billion a year in extra costs.

Do generic drugs work as well as brand-name drugs?

Yes. The FDA requires generics to have the same active ingredients, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand-name drug. They must also prove they’re absorbed into the body at the same rate and extent. Over 90% of U.S. prescriptions are filled with generics because they’re safe and effective.

Why aren’t biosimilars as common as generic drugs?

Biosimilars are complex biological drugs, not simple chemicals. They cost far more to develop and manufacture. Fewer companies can make them, and they face more regulatory hurdles. As a result, they’ve only reached 45% market share, compared to 90% for traditional generics.

Just had my pharmacist switch me to generic lisinopril last month-same effect, $3 instead of $120. I didn’t even notice the difference. Why are we still paying brand prices when the science says it’s the same thing?

It’s fascinating how market forces can be weaponized for public good. Generic competition isn’t just economics-it’s ethics in motion. When you strip away the branding and the marketing, you’re left with molecules. And molecules don’t care about patents. They just work. The real tragedy isn’t the high price of drugs-it’s that we’ve normalized paying for hype instead of healing.

What if we started valuing health outcomes over shareholder returns? What if we treated medicine like a public good, not a profit center? The data’s there. The solutions exist. It’s just willpower we’re missing.

People don’t realize how much they’re being scammed. The system’s rigged. Reverse payments? Product hopping? These aren’t loopholes-they’re crimes. And the FDA lets it slide because big pharma funds their next budget. Wake up.

Also, biosimilars aren’t ‘harder’-they’re just not being pushed. The same companies that blocked generics for decades are now blocking biosimilars. Same playbook. Different drug.

As someone who has worked in international pharmaceutical policy for over two decades, I can confirm that the U.S. model is uniquely inefficient. In Canada, the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board sets ceilings based on international reference pricing-simple, transparent, and effective. In Germany, the AMNOG process evaluates added therapeutic benefit before pricing. Neither system relies on chaotic, reactive competition.

The U.S. approach is reactive, fragmented, and vulnerable to manipulation. The Inflation Reduction Act is a step forward, but it’s still playing whack-a-mole with a sledgehammer. Structural reform is needed-not just negotiation, but systemic redesign.

Imagine this: you’re at a grocery store. You want a can of beans. The brand version costs $8. Then ten other brands show up-all identical-priced at 25 cents. You’d laugh, right? You’d call it a scam if someone tried to sell you the $8 can.

But when it’s a pill? Suddenly, it’s ‘innovation.’ Suddenly, it’s ‘R&D.’ Suddenly, we’re supposed to be grateful that Big Pharma lets us buy the same molecule for $15 instead of $150.

It’s not capitalism. It’s capitalism with a straight face and a lab coat.

Europe’s reference pricing is socialist nonsense. We don’t need to align our prices with France or Germany. We have the most advanced pharmaceutical industry in the world. If generics drive prices down, fine-but don’t let bureaucrats cap what American innovation is worth. We don’t pay Canadian prices for iPhones. Why should we for drugs?

Also, ‘reverse payments’ are just business contracts. If a company wants to settle litigation, that’s their right. The FTC is just jealous they can’t control the market.

Let me tell you something I’ve seen firsthand. I work in a rural pharmacy. We’ve got folks on fixed incomes who skip doses because they can’t afford the brand. One lady was splitting her 20mg metformin pills because the 10mg cost $40. We switched her to generic-$4 a month. She cried. Not because she was happy, but because she realized she’d been suffering for years thinking it was the only way.

It’s not just about money. It’s about dignity. And the fact that we’ve turned medicine into a negotiation between insurers and pharma while patients bleed out in the middle? That’s the real scandal.

And don’t get me started on authorized generics. That’s like the original company opening a fake competitor just to keep prices high. It’s disgusting.

Generic manufacturers are crying wolf. If you can’t make a profit on a $0.10 pill, maybe you shouldn’t be in the business. The market rewards efficiency-not excuses. Stop whining about ‘complexity’-if you can’t compete, get out. Patients don’t care about your balance sheet.