What Happens When Your Sodium Levels Go Wrong in Kidney Disease

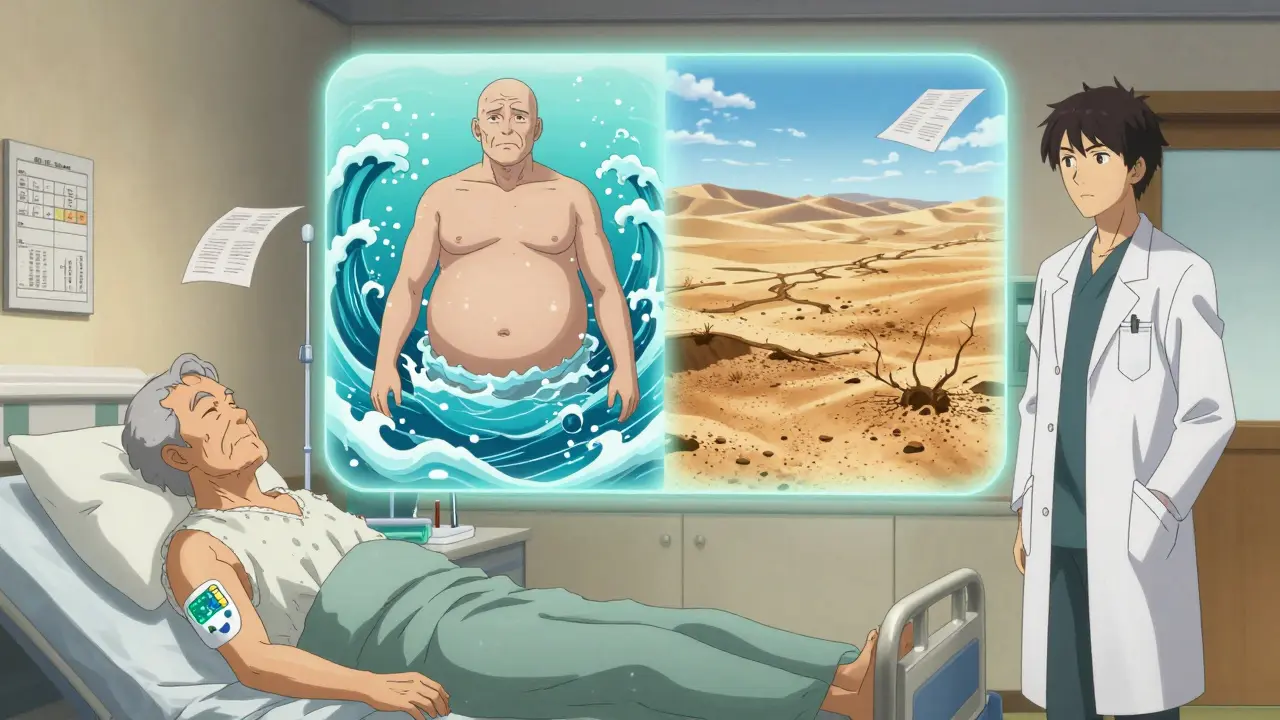

When your kidneys start to fail, they don’t just stop filtering waste-they lose their ability to keep your sodium and water in balance. That’s when you get hyponatremia (low sodium) or hypernatremia (high sodium). These aren’t just lab numbers. They’re dangerous, silent threats that can lead to falls, confusion, brain damage, and even death-especially if you have advanced kidney disease.

Why Your Kidneys Can’t Keep Sodium in Check

Your kidneys are like precision water and salt managers. Every day, they adjust how much sodium you pee out based on what you eat and drink. But when kidney function drops below 30% (stage 4 or 5 chronic kidney disease), that system breaks down. You can’t make concentrated urine anymore. You can’t flush out extra water fast enough. And your body starts holding on to fluid like a sponge.

Early on, your kidneys still handle normal sodium intake-but they need to produce way more urine to do it. As damage grows, even small changes in water intake can throw your sodium levels off. That’s why people with late-stage kidney disease often end up with hyponatremia even if they’re drinking just a little too much water.

Hyponatremia: The Silent Killer in CKD

Hyponatremia-serum sodium below 135 mmol/L-is the most common sodium disorder in kidney disease. About 60-65% of cases are euvolemic, meaning you’re not swollen or dehydrated, but your body just can’t get rid of water. Thiazide diuretics, often used for high blood pressure, make this worse. They’re less effective in advanced CKD but still cause sodium loss.

Here’s the scary part: people with hyponatremia and CKD have nearly twice the risk of dying compared to those with normal sodium levels. Studies show a 1.79 times higher risk of death just from mild hyponatremia. It’s linked to cognitive decline, slower walking speed, falls, broken bones, and even osteoporosis. In one Japanese study, older CKD patients on strict low-sodium diets had more hyponatremia-not less-because their kidneys couldn’t excrete water without enough solutes to pull it out.

Hypernatremia: When You’re Too Dehydrated

Hypernatremia-sodium above 145 mmol/L-is less common but just as dangerous. It usually happens when you’re not drinking enough, especially if you’re elderly, confused, or have trouble accessing water. In advanced CKD, your kidneys can’t concentrate urine to save water, so you lose more fluid than normal. Even a small drop in water intake can spike sodium fast.

Correction is tricky. Draining sodium too quickly can cause brain swelling. Doctors aim to lower sodium by no more than 10 mmol/L in 24 hours. That’s slower than in healthy people. Many patients don’t realize they’re dehydrated until they’re dizzy, confused, or in the hospital.

Three Types of Hyponatremia in Kidney Disease

- Hypovolemic hyponatremia (15-20% of cases): You’ve lost both sodium and water, but lost more sodium. Common causes: diuretics, salt-wasting syndromes, or vomiting/diarrhea.

- Euvolemic hyponatremia (60-65%): Your total body water is high, but you don’t look swollen. This is the classic CKD problem-your kidneys can’t excrete water, even if you’re not overhydrating.

- Hypervolemic hyponatremia (15-20%): You’re swollen (edema) from heart failure or nephrotic syndrome, and your sodium is diluted. This is common in late-stage CKD with fluid overload.

What Not to Do When Managing Sodium Imbalance

Many doctors treat hyponatremia the same way in everyone. That’s a mistake in CKD. Giving too much IV saline or correcting sodium too fast can cause osmotic demyelination syndrome-a rare but devastating brain injury that leaves people locked-in or paralyzed. Retrospective studies show 12-15% of these cases happen in CKD patients because standard protocols were applied without adjusting for kidney function.

Also, avoid thiazide diuretics if your eGFR is below 30. They’re useless for lowering blood pressure at that point and just raise your hyponatremia risk. The FDA has issued warnings about this. And don’t use vaptans (vasopressin blockers)-they’re approved for hyponatremia but don’t work in advanced CKD because your kidneys can’t respond to them.

How to Actually Manage It

Fluid restriction is the first-line treatment-but it’s not one-size-fits-all. For early CKD, 1,000-1,500 mL/day is fine. For stage 4 or 5, cut it to 800-1,000 mL/day. That’s less than four standard water bottles. Many patients think “drink plenty of water” applies to them. It doesn’t.

Sodium intake? Don’t go overboard, but don’t starve yourself either. A 2023 study found that patients on ultra-low sodium diets (under 1,500 mg/day) had higher hyponatremia rates. Aim for 2,000-2,500 mg/day unless your doctor says otherwise. Too little sodium means your kidneys can’t make dilute urine-and you can’t flush out water.

For salt-wasting syndromes (5-8% of advanced CKD patients), you may need 4-8 grams of sodium chloride per day. That’s 1-2 teaspoons of salt-taken orally, not in food. This isn’t about flavor. It’s about survival.

New Tools and Better Care

In 2023, the FDA approved a new sodium-monitoring patch for CKD patients. It measures sodium levels in your skin fluid continuously and correlates 85% with blood tests. No more weekly lab visits. It’s still new, but it’s changing how we track these imbalances.

Best outcomes come from teams-not just nephrologists. Dietitians help patients understand how to balance sodium, potassium, protein, and fluid without getting overwhelmed. Pharmacists catch drug interactions. Primary care doctors monitor symptoms. One study showed a 35% drop in hospitalizations when all four worked together.

What You Should Ask Your Doctor

- What’s my current eGFR? How does that affect my fluid and sodium limits?

- Am I on a diuretic that could be making my sodium worse?

- Should I be tested for salt-wasting syndrome?

- Can I get a referral to a renal dietitian?

- Are there any new monitoring tools I should know about?

Why This Matters More Than Ever

Over 850 million people worldwide have chronic kidney disease. That number is rising fast-29% more by 2030. Sodium disorders are now part of the disease, not just a side effect. In the U.S., hospital stays for these imbalances cost $12,500 to $18,000 each. In Asia, hyponatremia is even more common, possibly because of stricter dietary rules.

This isn’t about avoiding salt on your steak. It’s about understanding how your kidneys work-or don’t work-and adjusting your life to match. You don’t need to be a scientist. But you do need to know your limits. And you need your care team to know them too.

Bottom Line

Hyponatremia and hypernatremia in kidney disease aren’t normal. They’re warning signs. They’re linked to higher death rates, brain damage, and broken bones. Fixing them isn’t about giving more salt or more water-it’s about matching your intake to what your kidneys can handle. That means working with your team, tracking your symptoms, and never assuming standard advice applies to you. Your kidneys may be failing, but your brain still works. Use it to ask the right questions.

Can drinking too much water cause hyponatremia in kidney disease?

Yes. In advanced kidney disease, your kidneys can’t flush out excess water, even if you’re not drinking a lot. Drinking more than 800-1,000 mL per day can dilute your sodium levels, especially if you’re on a low-solute diet. This is why fluid restriction is often more important than sodium restriction in late-stage CKD.

Is low sodium diet always good for kidney disease patients?

Not always. While high sodium worsens blood pressure and swelling, too little sodium (under 1,500 mg/day) can impair your kidneys’ ability to excrete water, leading to hyponatremia. Most patients do best with 2,000-2,500 mg/day, unless they have a salt-wasting condition. Always check with your dietitian before cutting sodium aggressively.

Why are thiazide diuretics risky in advanced kidney disease?

Thiazides stop working when eGFR drops below 30 mL/min/1.73m². But they still cause sodium loss in your urine, which can trigger hyponatremia. The FDA warns against using them in advanced CKD. Loop diuretics like furosemide are safer and more effective at that stage.

Can hyponatremia cause permanent brain damage?

Yes-if corrected too quickly. Rapid sodium increases can destroy the protective layer around brain cells, causing osmotic demyelination syndrome. This can lead to paralysis, difficulty speaking, or locked-in syndrome. Correction should never exceed 8 mmol/L in 24 hours for CKD patients.

What’s the most common mistake doctors make with sodium in CKD?

Applying standard hyponatremia rules to CKD patients without adjusting for reduced kidney function. For example, giving IV fluids or correcting sodium too fast. Experts say the biggest error is failing to recognize that CKD patients can’t excrete water like healthy people-even if they’re not swollen.

Are there new ways to monitor sodium levels at home?

Yes. In 2023, the FDA approved a wearable patch that measures interstitial sodium levels continuously. It correlates 85% with blood tests and helps catch imbalances before symptoms appear. It’s not yet widely available, but it’s the first step toward real-time monitoring for CKD patients.

This post is basically a 2000-word lecture on why doctors are clueless. I’ve got CKD stage 4 and my nephrologist still tells me to drink a gallon a day. Like bro, I’m not a camel. I’m barely keeping my sodium from crashing. Why are we still doing this?

There’s a profound irony here: we treat kidneys like broken pipes, when in reality they’re more like sentient negotiators caught in a collapsing economy. The body doesn’t ‘fail’-it adapts, often in ways we misinterpret as pathology. When sodium drops, it’s not a defect-it’s a survival protocol the brain has been screaming at the kidneys to execute. We’ve pathologized adaptation. We call it disease because we don’t yet understand the language of imbalance.

I’ve been on dialysis for 3 years and this is the first time someone actually explained why I can’t just chug water like I used to. My wife thinks I’m being dramatic when I say I’m scared to drink more than a cup at a time. Now I’ve got links to show her. Thank you. 🙏

Fluid restriction is the real villain here. Not salt. Not meds. Just too much H2O.

i just found out my dad has stage 5 and i had no idea how dangerous this was. i thought low sodium = good. turns out its the opposite? i need to talk to his doctor about this. thanks for sharing this

Ah yes, the classic Canadian advice: 'Drink more water!' as if our kidneys are still on vacation. In India, we call this 'Western medical arrogance.' My uncle had hyponatremia after following his American doctor’s advice to drink 3L/day. He ended up in ICU. Turns out, your kidneys don’t care about your Fitbit hydration goal. They only care if they can still function. And when they can’t? You don’t get to be a hydration guru anymore.

Is that new patch FDA-approved? Can I get one? I’d pay $500 for a device that tells me I’m not dying every time I drink a glass of water. 😅

Let me get this straight-some guy in Canada says we shouldn’t drink water? Next they’ll tell us not to breathe oxygen. This is why America’s healthcare is a joke. In my day, we drank water like normal people and our kidneys worked. Now we’re all walking around afraid of H2O? What’s next? No carbs? No sunlight? I’m starting to think this whole CKD thing is just Big Pharma’s way of selling patches and vaptans.

I read this whole thing while crying in my car. My mom died last year from something they called 'fluid overload'-but no one ever told me it was because she was trying to follow the 'drink 8 glasses' rule. I wish someone had said: 'Your kidneys are broken, stop treating them like they’re not.' This post? It’s the obituary I wish I’d had before she went.

Just a quick note-thiazides are a no-go below eGFR 30, but I’ve seen so many GPs still prescribe them because it’s 'what they’ve always done.' Please, if you’re on one and your eGFR is low, ask for a switch to furosemide. It’s not a big deal, but it could save your brain.

I used to be the guy who drank 3 liters of water a day to 'flush toxins.' Now I’m the guy who measures his intake in sips. Funny how your body changes your beliefs when it’s literally trying to keep you alive. Also, the patch thing? That’s the future. I’m already waiting for my pre-order.

We’re not just managing sodium-we’re negotiating with our own biology. 🌱 Your kidneys are the last diplomat in a failing government. They’re trying to keep peace between water, salt, and your brain. When you flood them, they don’t rebel-they collapse. And when they collapse? The brain pays the price. This isn’t diet advice. It’s a cry for humility from your own cells.

This is the most scientifically accurate and culturally ignorant document I have ever read. In South Africa, we do not have the luxury of 'FDA-approved patches.' We have one nephrologist for 500,000 people. We do not have dietitians. We do not have 'fluid restriction counseling.' We have mothers who give their children water because they are thirsty. And then those children die. This post reads like a luxury pamphlet from a clinic in Toronto. The real crisis is not hyponatremia-it’s systemic neglect. You want to save lives? Fix the system. Not the water bottle.